I started writing this piece in JFK airport, Terminal 7 to be exact. Up until the day before I didn’t know a Terminal 7 even existed and I certainly didn’t expect to be sitting there waiting on a plane on a Monday in January.

Unexpected trips to the airport are rarely a good thing in my experience. I have yet to have a romantic surprise of an all-expenses paid trip to a long-awaited destination, when my bags have been packed and my schedule has been cleared for the week to come. Since moving to New York from Ireland ten years ago, this is the second unexpected trip. Both were for funerals. This time, it’s for the funeral of a friend.

My cursor has been flashing at me for what seems like an hour. What can I say about my friend – about her death – that can express what I am feeling? I can tell you that the she was the same age as me, how vibrant she was, that she was a runner, that she practiced yoga. I can use the word “heartbroken”, even the word “crushed.” But there are some things that are almost unreachable by language, that live outside the realm that words can touch. As a writer, I find those are the things I want to reach the most, that I have to at least try.

So, let’s start by talking about my friend. She was a relatively “new” friend and by that I mean she didn’t fall into the category of so many of my friends that I’ve known since I wore a school uniform. We met twelve years ago – both of us in our mid-thirties – and I was friends with her brother first who was my yoga teacher. I was at a difficult time in my life and my therapist had urged me to give yoga a go. Dutifully, I had tried classes at my gym, at other gyms, at a studio in town. Mostly, I found big classes with women who were younger than me and more flexible than me who moved through poses at light speed. They bent themselves into shapes my body couldn’t even imagine and they did it without breaking a sweat – which was just as well really, because they all seemed to be wearing a lot of makeup. Like Goldilocks, I persisted until I found a class that was just right – a small class, close to home, every Sunday morning, held in a studio that was a haven of stillness and space from the rest of the week.

The class became important to me and right from the start I wanted to be friends with my teacher – he was wise, kind and funny too, not a combination I’d come across all that often. And when a cyst I had on my ovary ruptured during one of his classes and he took me to the A&E in an ambulance, I got my wish to know him better, albeit not in the way I’d imagined. While I was recovering in hospital after surgery, he came to visit me and told me about his sister who had been through a similar experience. He thought we had a lot in common, he thought we might get on well.

We got on well. From our very first meeting I distinctly remember having the feeling that I’d always known her – there was an ease about her that allowed me to be totally, fully myself. My first experience of meeting her bore out what I would experience again and again throughout the years of our friendship; her kindness, her caring, her generous sharing of her own experience to help someone else. Like her brother, she was wise and funny – a lightness and a depth at the same time. And maybe it was because of our shared medical history, or maybe just because of who we both were or the time we were at in our lives, but we seemed to bypass being acquaintances and fast-track straight to friends.

She became a regular at the Sunday yoga class too. A small group of us formed – including her brother – who started to meet up after class, who became friends, who spent hours talking about all manner of subjects. We did other yoga classes together, day and weekend retreats. It was a special time for me and I know it was for my friend too, a time she mentioned she had been thinking of fondly in one of her last messages to me the Sunday before she died.

Two years later, I moved to New York and you might think the pressure of the distance would be too much for a fledgling friendship like ours, but in many ways, it made the connection stronger. My friend was someone who actively maintained her friendships – something I try and do myself – and I don’t think there was one visit home when we didn’t meet up and spend time together, even once when she had broken her arm in a nasty accident. Four years after I moved, together with her brother and his wife, she came to New York for my wedding – something that meant more to me than I think any of them knew. On my trips to Ireland, we met up for coffee, walks, lunches, sometimes we did yoga together – ordinary things, little things, unremarkable in their nature except, it turns out, the little things are the big things after all.

You’ve probably heard the saying “make new friends but keep the old, one is silver, one is gold.” I first heard it in primary school, and the inference is clearly that old friends have the gold position. I’m not saying that I disagree with that at all, of course there’s something incredibly special – irreplaceable – about those friends who went to your childhood birthday parties, who know your family, who can still pull out that embarrassing story from your J1 experience, who you could dial in the middle of the night without thinking twice, should the need arise. But there is also – in my experience – something equally special about those friends we make when we are adults already, when we are fully formed and we actively choose our friends in a different way. The friends I choose to expand my life to include in my 30s or 40s are just that, chosen. We don’t become friends because we live next door to each other or sit next to each other in class – or, at least, not just because of those things. We become friends because we see something in that person that interests us, that we would like to have in our own lives. As we become more ourselves – certainly, as I have become more myself – I have gravitated towards people who live their lives in a way that I want to live mine. And these friends are shiny and gold too.

She got sick, my friend, that’s what happened. In the middle of the pandemic when all of our worlds were upside down, she was diagnosed with cancer. Something that makes me sad is that I didn’t know right away, that in the craziness of that time and the haze of my own Covid recovery I didn’t notice that she hadn’t responded to my last WhatsApp message – something so unlike her – that I hadn’t followed up to see if she was okay. When I received a message from her a few months later telling me about her illness, she was concerned I would be hurt that she hadn’t told me before, it was hard, she said, to tell people, that every time she went to send the message she would see a photo of me and my wife on Facebook, happy or on holidays and she would wait a little longer. I had tears in my eyes reading her message and I have tears in my eyes thinking about it now – how even then, with all she was going through, she was caring for others. Of course it was hard to tell people, of course I understood. I didn’t care who knew what, when. I just wanted to be there for her and support her. I just wanted her to get better.

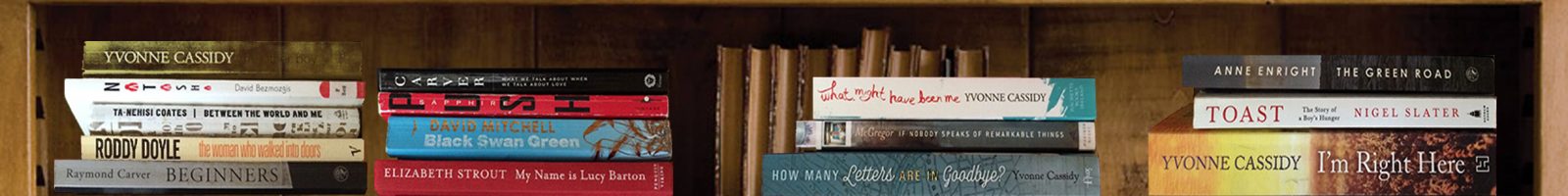

The last 12 months of our friendship – of her life – were the closest we’d ever been. Looking back over our WhatsApp messages – several times a week – we talked about everything, sharing in an even deeper way than we had before. We swapped photos of New York and Sandycove, of the Atlantic and the Irish Sea, we made time to Zoom – sometimes with her brother, sometimes with just the two of us. We made plans for places to go together when she got better – a seafood restaurant in Long Beach, the U.S. Open, we even talked about running a 5K. Through the ups and downs of scan results and a variety of treatments, she was relentlessly optimistic. She was grateful. When she couldn’t run with her beloved running club, she was grateful for the walks she could take, for being able to go sea swimming with her brother. When she could no longer do those things, she was grateful that she could meditate, for the books she was reading – for a nice meal she had cooked herself. Cancer might have been attacking her body but she didn’t let it get a foothold on her spirit; she was the person she had always been – curious, kind, always asking about others, always so interested in life, in living it.

I’m finishing this piece on the way back to New York, in another airport, Reykjavik this time, waiting on my connection to JFK. I find myself reading back over those WhatsApp messages and one of the things that makes the tears catch is that her name – always so close to the top – is disappearing down the list now, that I have to scroll down to find our message thread. Her last message to me is one of the shorter ones, where she talks about setting up a time to speak when she feels stronger. Reading it, I am reminded of the words of the priest at her funeral – also, a close friends of hers – when he said that while she was in pain, she didn’t suffer all that much because of her attitude, because of who she was. I’ve been thinking about that all week – the difference between pain and suffering, because he’s right, because it’s true, because there is a difference. My friend chose to believe she would get better and do everything she could to make that happen. She chose gratitude over despair, she chose love and connection over isolation during what must have been her darkest days. And sitting here, in this airport, I am thinking of how again – even in her death – I am learning from her, how I will always learn from her how I want to live my own life.

I do and don’t want to end this piece. Ending this piece means – in some way – a kind of goodbye to my friend that I am not yet ready to say. So before I do, I’ll tell you about our last meet up together, face to face, last August. We went for a walk by the sea in Sandycove, we saw a rainbow, we got fish and chips and came back to my hotel room to eat them because it had started to rain. When we said goodbye, it was an easy one because we thought we would be seeing each other again in a few days, with her brother and another dear friend from our yoga group – neither of us knew she wouldn’t be well enough to join us that time. What I remember is walking her down to the door of my hotel, laughing at not being able to hug and waving goodbye instead. And afterwards, walking back upstairs, reflecting on all we’d shared, I had the feeling that I always had after spending time with her – I felt nourished, I felt full.

As always, we’d run out of time – there was still so much left to say. As always, I was already looking forward to the next time I would see her.

And just like always, I still am.

Michele Bontempo

Yvonne Cassidy

Joan Arenstein

Yvonne Cassidy