Last year, I was honoured to be asked by Colum McCann to take part in the launch of his non-profit project Narrative 4 and to write 800 words on the first assignment: “How to be a man.”

My take on this is below and you can read pieces from other writers and find out more about Narrative 4 here: www.narrative4.com

Last night was 86 nights. I know it’s 86 because of the row of dents in the wallpaper. The first dent is deeper because it’s in the squashy patch, under the windowsill. I always make the dent before I cover Betty’s ears, even though I know she can’t hear because they’re made of fur.

I keep thinking Mammy will see the dents when she changes the sheets, but she hasn’t changed the sheets. She changed the sheets every two weeks before, but maybe I’m remembering wrong.

The day Mrs Taylor catches me sleeping at school I don’t know I’m sleeping until I’m awake and the other girls are laughing because of the wet on my cheek and my copy. Afterwards, I have to stay back.

‘How’s everything at home, Grainne?’ It’s Monday so she’s wearing her beige jumper and brown blouse. Her breath smells cigarettey.

‘Grand.’

Lisa went on ahead to tell her Mam to wait for me and I hope they do because it’s raining.

‘How’s your Mam?’

‘Grand.’

She nods. ‘You’d miss not having a man around.’

In the car, Lisa’s making faces at her brother but I don’t join in because I’m thinking about what Mrs Taylor said. At home, I start the list:

1. Drive the car.

2. Fix things.

3. Mow the grass in the summer.

4. Make her laugh.

5. Give her money.

6. Put the bin out.

I think that’s everything, except for sleeping in her bed and I have my own bed. The car was taken away after his accident and nothing needs to be fixed and it’s not the summer.

That leaves the laughing and the money and the bin.

I’m no good at jokes, I’m always forgetting, so I learn the ones in the back of Whizzer & Chips by heart. That night, I try one.

‘How much does it cost to keep a polar bear as a pet?’

She looks at me as if I’m far away, even though I’m only on the bed.

‘We’re not getting a pet, Grainne.’

‘It’s a joke, Mammy. Guess!’

She shrugs.

‘Nothing – they live on ice!’

I laugh. She smiles and says ‘that’s funny,’ but her smile doesn’t go as far as her eyes. I try another joke in the morning, about walruses. She calls me a joker. She doesn’t laugh.

Thursday is bin night.

In the dark, the garage is scarier because you can’t see the spiders. The handles of the bin are too far apart. When Daddy lifted it, he made it easy. I imagine he’s there, giving me super powers of strength. When the bin falls over it makes a big crash, and I think Mammy will come in and give out but she doesn’t hear it.

Tonight, is night 87.

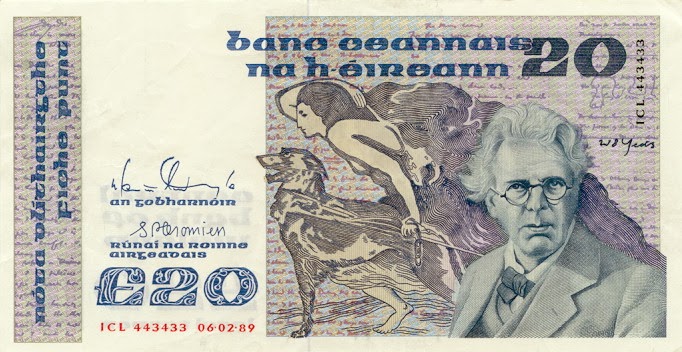

The money slides in my shoe. The pointy corners where it’s folded, catch in my sock. I didn’t want it falling out of my pocket. I imagine Mrs Taylor saying, ‘Where did you get that twenty pounds from, Grainne?’ and my face going red and everyone knowing I’m a bad girl. And I’m not really, I don’t want to be. Anyway, Lisa’s Mam still had four twenties left.

Daddy always left the money in the kitchen, behind the windmill from Holland, but I can’t put it there, so I sneak into Mammy’s room. The smell is like Daddy, but not like Daddy, and I know it’s because the laundry basket still has his socks and shirts inside. The black patent bag she’s used every day since the funeral is on the floor. Her purse has a zip and it sticks but then it’s open.

That night, tucking me in, she gets into bed with me and Betty. She’s already crying. She still has her shoes on. It’s squashy and hot.

‘I need money, Mammy. For school.’

‘Now?’

‘We’ve got swimming tomorrow. It’s £1.25.’

Swimming’s not for two weeks.

‘I’ll leave it out later, love.’

‘You might forget. Please, Mammy.’

She pushes herself up, wipes her face. The mattress goes down like a valley and then flat. I hear her in her room, opening her bag. I think I hear the zip getting stuck but I’m only imagining. When she comes back she has a pound note, two ten Ps and a five.

‘There.’ She wraps the coins in the money and puts it on the chest of drawers.

‘Thanks, Mammy.’

She kisses me on the hair. She’s stopped crying. She must have seen the twenty. It must have worked.

After she turns out the light, me and Betty lie there, listening to her on the landing, the stairs. We must have fallen asleep, because then I’m awake, and then I hear her.

I find the right place on the wall, dig my nail in.

87.

I cover Betty’s ears.