I am thirteen and I am on my way to Wesley in my friend’s dad’s car. It’s Hallowe’en and my first disco. We are dressed up as cats. When the last friend we pick up gets in the car she’s in normal clothes – she’s just found out it’s not fancy dress after all. My friend in the front seat is panicking, trying to scrub her eyeliner drawn on whiskers off with a tissue and spit – I’m glad I’m only wearing a mask.

Inside it’s full, a crush. Immediately, I hate it. I want to leave and do what we always do on Hallowe’en –wait until my friend’s dad goes to the pub and watch horror films – but I know it’s important to pretend to like it here. Pretending – I’ve learned by thirteen – might not always feel good, but it makes things easier in the end.

I follow my friends through the crowd, but a group of boys cut between us, separating me from them. They’re all around me, I can’t get through. The stupid black jumper I’m wearing as part of the cat outfit is much too hot, I can feel a bead of sweat rolling down– I hope no-one can smell it. I try and step around the boy standing in my way but he steps the same direction I step. He’s taller than me but then again everyone is taller than me.

-How old are you? he says.

I blurt out my real age – I don’t know yet, how not to answer something I am asked

-Thirteen? He turns to his friends. – Did you hear that? They’re lettin’ fuckin’ thirteen year olds in here now.

Then back to me.

-You’ve probably never even shifted anyone have you?

They are all laughing, faces half disco lights, half dark. Thirteen is too old to cry but knowing that might not be enough to hold back the tears and just as I’m bracing myself for what is about to come, I feel my friend’s hand on my arm, pulling me through them. And that’s when I hear it, those first few bars, that riff, a voice – your voice. And those stupid boys don’t matter anymore.

Did I know what Mandinka was about then, that night on the dancefloor feeling the beat pulse through the thin soles of my suede Simon Hart slip-ons? No, I’d no idea and yet, some part of me did know – I do know – some part of me could feel the meaning in a way I’d never felt a song before. This wasn’t a song about boys or breakups – this was a song about power.

Later, I see you on Top of the Pops, The Late, Late Show – I have never seen anyone like you before and now that I’ve seen you, I can’t stop looking. Someone makes me a tape of the Lion and the Cobra and I listen to it everywhere – in my room, in the back of my parents’ car, sometimes sharing headphones at lunchtime in school. As long as my Walkman batteries hold out, your music can take me away, take me somewhere else, take me to the place it takes you.

I’m fifteen when it comes out – Nothing Compares 2 U. This time I buy the album, I want to be able to see your face on the cover whenever I want. The first time I see the video I am babysitting – me and a friend. The people we are babysitting for have a bigger TV than our one at home and you fill the whole screen up, your face does, it’s like you’re in the room with us. My friend is talking – how can she be talking while you are singing? – but I’m not listening to her. There is no room for anything else, except you.

What I’m feeling in that moment – I can see it now, from this distance – is love. Love for you, yes, but love too for someone else, a girl in my class, a new friend, a feeling that is different than with my other friends, a feeling I can’t name. At fifteen, I don’t know that it will be years – almost two decades – before I can name it, before I will be brave enough to do that, but for the five minutes of your song, it’s enough to feel the possibility of it, the freedom of it, to feel something other than fear. To know that this love might just be okay.

Reading about you now – after what’s happened – there’s so much talk again about you ripping up the Pope’s photo. And I remember that – of course I do – your photo on the front page of the paper, people on the radio saying – my parents saying – how crazy you were, how wrong that was. What I remember mostly about that time is getting into fights with them – defending you – even though I didn’t really know what you meant, what it was I was defending. But I knew by then – at eighteen – that the religion I’d learned at school only seemed to get in the way of any inkling of something that just might be God. And I knew intuitively that I could trust you – trust the truth I’d always found in you.

It’s years later. I’m thirty five, in fact it’s the weekend of my 35th birthday. I’d had plans to go to a concert in Belfast with friends but at the last minute I decide to come here, to a retreat centre in Wicklow. The retreat is from Friday to Monday and the topic is “Shame.” The twenty five or so other people here are like me – adults who were sexually abused when they were children. It’s six months since I’ve secretly been coming to weekly group therapy at Dublin based charity One in Four and I still have a hard time putting those words together in a sentence. Part of me wants to stay in denial but the other part knows that facing this truth is my only choice – that it’s not really a choice at all.

It’s Monday, the last day, and these three days have changed me in a way I can’t yet explain. I don’t know yet on that Monday in May that I am on the cusp of finally publishing my first novel, of accepting my sexuality, of meeting a woman in New York who will later become my wife. But sitting in a circle on the wooden floor, with light streaming through the long windows, I do know that something inside me has shifted, is forever changed.

We go around the circle, trying to find words to share what this weekend has meant to us. Across from me, a woman asks if she can sing, rather than talk and in the silence, she starts, faltering at first, then, her voice getting stronger: Thank You For Hearing Me.

It’s years since I’ve heard it – the last album of yours that I had bought – and it’s not your voice I’m hearing now, but yet it is, every beat of it, is you. Someone starts to sing with her and then we all sing together, our voices, blending with yours, our tears, with yours. And the first thing I do when I get home is dig out your CD from a box in the spare room and find it; that track. I live alone and I play it loud, over and over and over. Your voice fills up my little house, I open the windows so it fills my garden. You fill up the places in my heart the retreat has cracked open – the places that need to heal.

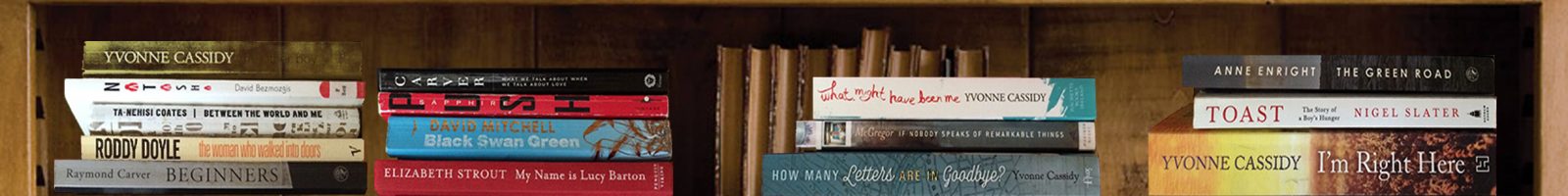

I am 49 sitting in my office when I get a text from my wife with the news. It’s two days since I finished reading your memoir and I haven’t started another book yet, haven’t been ready to replace your voice in my head. With your guidance, I’ve been revisiting your albums, the songs you liked, your favourites. On my Spotify, The Healing Room is half way through, paused from when I got off the lift at work that morning, ready to take me home.

I’ve cried a lot since that day – it’s surprised me, how much I’ve cried – and I’m crying, now, writing this, as I write to you and write to the part of myself who feels so lost without you. And yet, I know that what’s more important than you being gone is what you left behind, what you left us all: the maps you gave us to navigate the roads we don’t always want to travel – the roads we sometimes don’t even know we are on – the truth that if we follow it, will always light even the darkest roads ahead.

Rest easy, Sinead and thank you.