The first time I heard the word “lezzer” I was playing a game called “Home Truth.” My friends and I played every day for years and that day two of us were hiding in a hedge between two gardens. A boy cycled up the driveway behind us. He was a boy we never asked to play and usually he was a quiet boy, but not that day.

“Lezzers!” he shouted. “Youse two are lezzers!”

My first concern was that he had given up our hiding place. But when my friend pushed herself far away from me and made a pukey face, I knew a lezzer must be something really bad. And that my next action was important. “No we’re not!” I shouted and pushed myself so deep into the hedge, away from her, that the branches scratched my arms. I don’t remember the rest of the game, if we got caught or “saved ourselves,” but I do know that neither of us said anything about the incident to the others.

By my first year in secondary school, I knew, of course, what “lezzer” meant although I don’t remember who ever told me. At lunchtimes, we speculated about who might be one. Apparently one in ten girls were, some people said one in four. That meant there could be twenty five in our year. It seemed impossible that these alien girls could walk among us, preying on us and I don’t know if I fully believed it, but it didn’t stop me hypothesising, safe in the knowledge it wasn’t me.

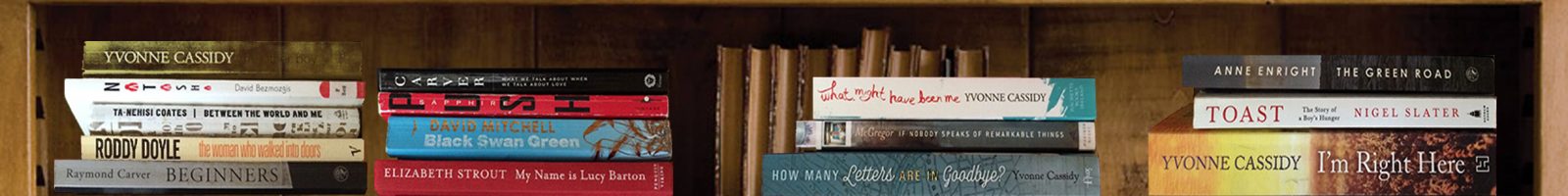

I gave this detail to my protagonist Rhea Farrell, in my new novel “How Many Letters Are In Goodbye?” Rhea is 17 and, like me, grew up in a small village in Dublin. But Rhea is younger than me and braver than me and has been through much, much more than me. For both Rhea and I, uncovering our sexuality is gradual. There’s no flashing sign, no letter in the post, only a series of small and bigger clues. Rhea is willing to look at these clues. At 17, I wasn’t.

Did you ever ignore something for so long you forgot you were ignoring it at all? That’s what it was like. And if a new clue sneaked into my view, something I didn’t want to bring into the light, it just became something else to hide in the dark. But when my life took some turns at the start of my 30s, turns that I never wanted it to take, the lights came on and they weren’t so easy to shut off again.

Looking back, this period was painful, lonely. I was terrified to speak to anyone – not family or friends, even my gay friends. Everyone knew me as straight –I knew me as straight – and I wasn’t even sure, I had to be sure. I started to go to a lesbian group in Outhouse, creeping up Capel Street with an excuse at the ready in case I was spotted. Sitting awkwardly at the table making small talk, I envied the younger girls – they brought girlfriends, held hands, kissed. They seemed so much lighter, like somehow they’d put down the boulder of shame that weighed so heavily on me, or never picked it up at all.

They influenced my novel, those girls. They helped me to show how naturally Rhea’s sexuality unfolds for her, how pure it feels. Being gay gets tangled up in debates about religion and debates about politics but really, in the end, it’s just about love.

For me, I had to get far away to shed that shame, as far away as New York. I found love there – it found me – and after years of knowing and not knowing, I finally knew. And it felt like freedom.

Love gives you strength, it gave me strength to tell the first person and the next. Once I started to tell people I didn’t want to stop. Each time I told someone, I reclaimed something, a part of myself I’d given away before I knew how important it was.

We live in New York – my wife and I – and the only time people look at us when we walk down the street holding hands is when we march in the Gay Pride parade. It might sound over the top, but after years of silence, there’s something about the crowds, the banners, all that cheering that’s very special, more than special – it’s a feeling I can’t describe.

And I wish that I could bottle that feeling, or make a tape and somehow show it to my 17 year old self. So she could see there’s no reason to worry, there’s nothing to be afraid of, that things will work out.

No matter how long it takes.

This article was originally published in The Evening Herald on Saturday 5th July. It was also published on the Independent Online on Monday 7th July and is available here: